Human Rights Workshops Explore Indirect Discrimination

In Panama, Peru, and Colombia, gender-based quarantine schedules created a culture of fear and risk for transgender individuals. With men allowed out of the house on certain days of the week and women others, gender-diverse persons faced an increased threat of persecution and discrimination by the state and the public. Human Rights Watch and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights were but some of the groups to note alarm. Just a few months after they were enacted, many of these laws were wiped from the books.

These gendered pandemic measures were an example of the practices and laws up for discussion at a February workshop hosted by the Human Rights Program (HRP) at Harvard Law School. The event, which focused on indirect discrimination resulting from the pandemic, with a particular emphasis on sexual orientation and gender identity, was one in a series of indirect discrimination workshops HRP has convened in the last year. In spring 2020, HRP hosted a virtual convening exploring indirect discrimination on the basis of religion with several former and current members of the UN Human Rights Committee. During the 2020-2021 academic year, HRP hosted two additional workshops drawing on other categories of indirect discrimination. Convened with Columbia Law School’s Human Rights Institute, the October 2020 workshop addressed indirect discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, laying the foundation for February’s discussion on the pandemic.

“One way to think about the purpose of indirect discrimination norms,” said one expert at the October convening, “is that they compel government, or other actors subject to the norms, to actively think about or know about the lives of people who are not like themselves.”

Indirect discrimination is a term that encompasses rules or laws whose intent may not be to discriminate against one group “on the face of it” but has the effect of doing so. In the workplace, for instance, a policy that requires employees to work on Saturdays may have severe effects for those of the Jewish faith, who observe Saturday as a holy day of rest. Indirect discrimination affects a range of protected groups on the basis of race, religion, and other factors.

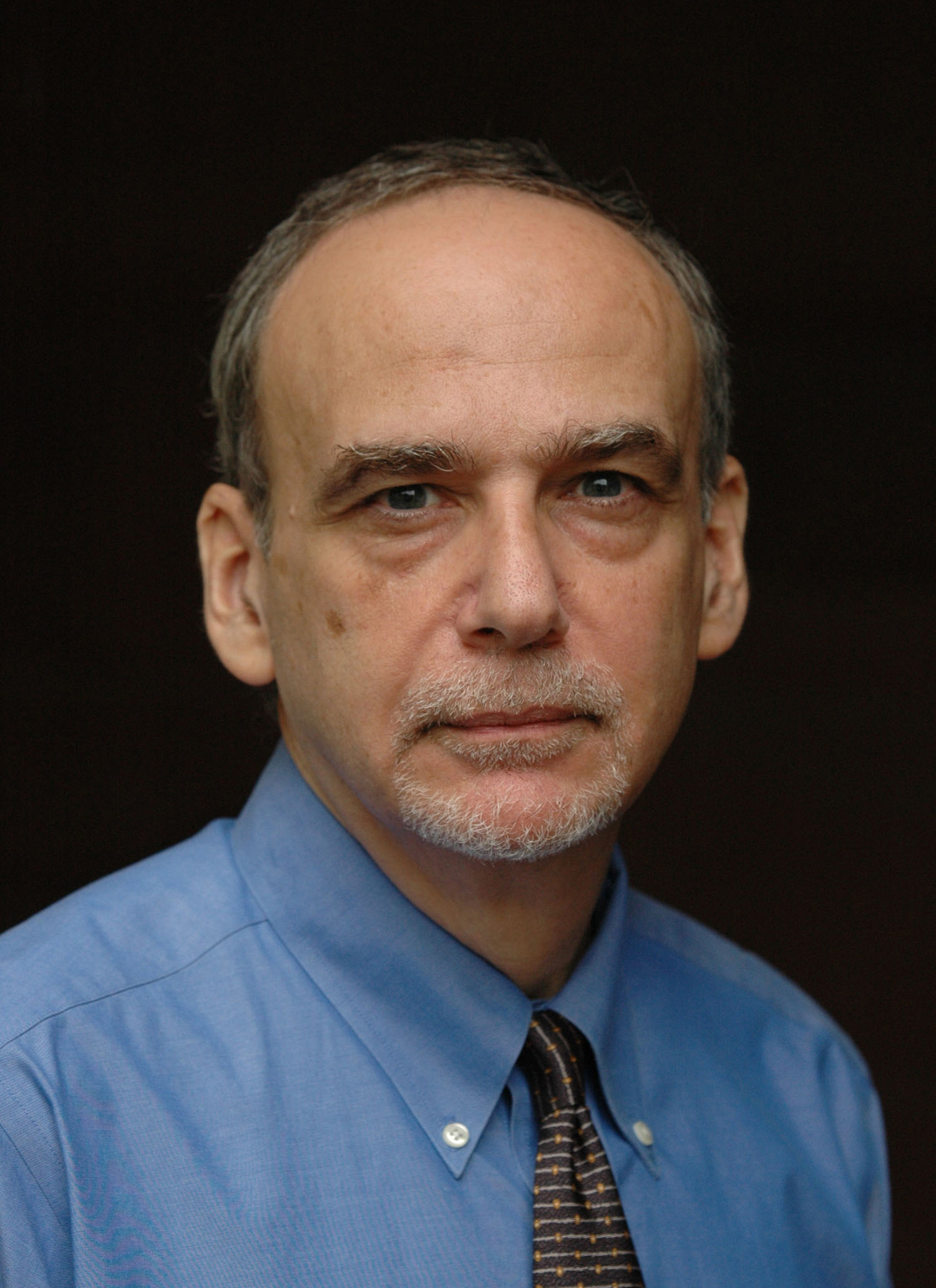

“It is easy to understand how intentional discrimination imposes disadvantages on certain groups,” said Gerald Neuman, HRP Co-Director and the Sinclair Armstrong Professor of International, Foreign, and Comparative Law. “Indirect discrimination, as opposed to direct, can involve unintended barriers that disproportionately hold back members of a group that may already be disadvantaged. How this concept should be applied in areas that are new for discrimination law, such as SOGI, raises important questions, like how narrowly groups should be defined or what unintended harms are disproportionate.”

A participant in this year’s workshops, Dorothy Estrada-Tanck, Assistant Professor of International Law at the University of Murcia, Spain and a former HRP Visiting Fellow, explained that indirect discrimination can be “hard to prove,” especially when biases “are so deeply rooted in the culture of the unequal societies in which we live.”

“This is key to understanding why it is so difficult to crystallize indirect discriminations in laws: it is extremely challenging to demonstrate that supposedly neutral legal provisions and practices actually create conditions of gender disadvantage and inequality at large,” said Estrada-Tanck, who is also a member of the UN Working Group on Discrimination Against Women and Girls.

The 2020-2021 workshops were jointly hosted by Neuman and United Nations Independent Expert on SOGI Victor Madrigal-Borloz, who is also the Eleanor Roosevelt Senior Visiting Researcher at HRP, where he works closely with Harvard Law School students on his thematic reports to the UN Human Rights Council and General Assembly.

“COVID-19 has presented a very specific magnifying glass as a case study for the mandate,” Madrigal-Borloz said in October. The Independent Expert noted extreme cases of direct discrimination, such as where “some states were actively using the pandemic as an excuse to persecute and achieve objectives that had become politically viable, such as Hungary’s denial of legal recognition of gender identity to trans persons, or Uganda’s targeted raiding of homeless shelters specifically dedicated to LGBT persons.” On the side of indirect discrimination, Madrigal-Borloz brought up the gendered quarantine measures, as well as all of the unanticipated ways that LGBT individuals might experience further hardship when compounded with other risk factors, such as homelessness and poverty.

February’s workshop featured participants from United Nations Special Procedures with a diversity of perspectives and mandates, as well as representatives of UN treaty bodies and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Because of the role of such experts, the conversation was oriented toward advocacy and the “promotion of rights,” Neuman said. Rather than reviewing and interpreting court cases involving indirect discrimination and rights violations, experts discussed how governments might build a better rights-respecting reality.

Throughout the year, participants considered questions such as, “How should the right not to be subjected to indirect discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity interact with the right to manifest religion or belief in practice?” In this vein, participants examined a struggle between protected groups in direct and indirect discrimination claims. In some examples of recent U.S. litigation, groups claiming discrimination on the basis of religion are at odds with actions that exclude LGBT individuals. The U.S. Supreme Court case, Fulton v. City of Philadelphia, for instance, debates the question of whether government-funded foster care agencies have a “right” to discriminate based on their religious beliefs, ultimately excluding LGBT couples from fostering children while still receiving government assistance.

With the recent focus on the pandemic, February’s workshop participants emphasized how both direct and indirect discrimination is magnified in health, especially when intersecting with sexual orientation and gender identity. While the pandemic has brought such intersecting discriminatory effects to the fore, questions around reproductive health and the way in which the medical field provides for or ignores gender-diverse individuals is a systemic issue that must be addressed using a rights-based response, many participants agreed.

Throughout the year, the dialogue highlighted the importance of intersectional thinking when talking about SOGI. One can’t talk about power without addressing poverty, gender, race, age, and the way all of these factors collide, said Madrigal-Borloz. Likewise, workshop participants constantly reflected on the position with which they approached an issue: were they considering whether discrimination was occurring on the basis of identity or activities? How did one affect the other?

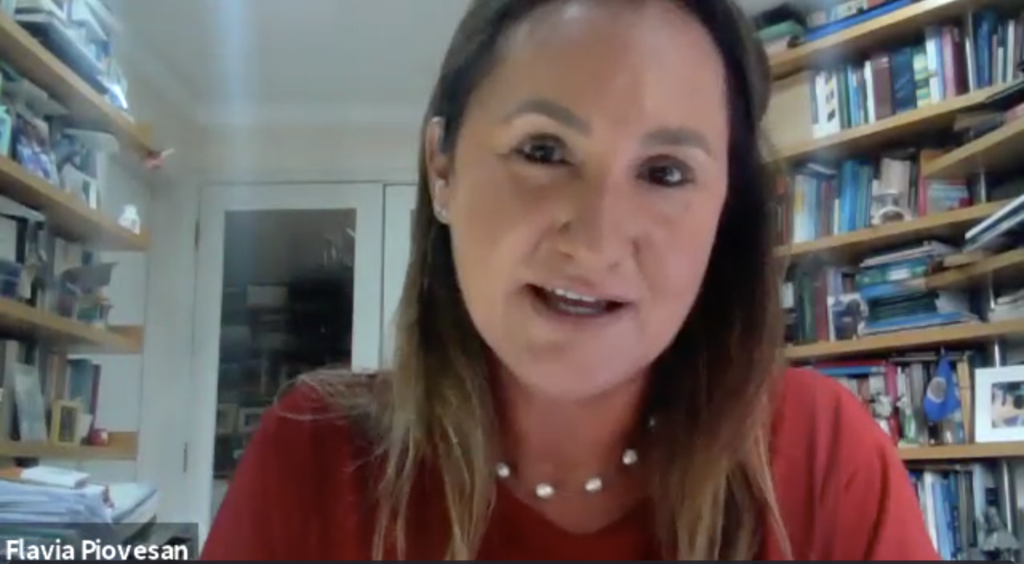

Flávia Piovesan, Commissioner and Rapporteur on the Rights of LGBTI Persons for the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) was a Visiting Fellow at the Human Rights Program in 1990. Writing about Indirect Discrimination against LGBTI Persons in the Inter-American Human Rights System for the February workshop, she noted that the Inter-American Convention against All Forms of Discrimination and Intolerance is “unique among international human rights treaties in its codification of the concepst of indirect discrimination.” This codification was useful to the Inter-American Commission in identifying and condemning the gender-specific quarantine measures, she noted.

“I think it’s really important that human rights has the capacity to evolve and acknowledge forms of discrimination that weren’t anticipated in an original law or treaty,” said Jessica Tueller, a 2021 Yale Law School graduate who will be working with Piovesan at the Inter-American Commission next year as a Robina Fellow and who collaborated with Piovesan on her paper. “

“For example, in the inter-American system, the Court and Commission began interpreting the rights to equality and non-discrimination in the American Convention and the American Declaration to prohibit indirect discrimination a decade before this concept was expressly defined and identified as a human rights violation in the Inter-American Convention against All Forms of Discrimination and Intolerance. And I expect the meaning of these rights will continue to evolve as the Court and Commission deepen their understanding of how indirect discrimination constitutes evidence of and is rooted in structural discrimination.”

Tueller likewise worked with Alice M. Miller, Co-Director of the Global Health Justice Partnership and Associate Professor of Law at Yale. Miller, who grounds her scholarship in how it could be useful to advocacy movements, spelled out several hopes for how such a discussion could “spin out into the world.” These recommendations included asking questions about how “law and legal frameworks” act as “structural determinants of health,” and in the case of the pandemic, how the state regulates public and private life in the name of health.”

In addition to inputs from academics, practitioners working to advocate for LGBT rights in civil society attended the workshop.

Geeta Misra, Executive Director of CREA, a feminist NGO based in New Delhi, India, noted that attendance at the workshop allowed her the space to talk with activists and scholars about crafting rights-based arguments.

“The concept of indirect discrimination has been really useful for me in thinking through how to position arguments claiming rights for the structurally excluded people in our work,” she said.

Working papers and an account of workshop proceedings from October 2020 were published this month, with February proceedings to follow. The October working papers include scholarship from Eva Brems, Professor of Human Rights Law at the University of Ghent; Mary Ann Case, Arnold I. Shure Professor of Law at the University of Chicago, Neuman, Miller, and others.

“This was an invaluable opportunity to concentrate on these issues with a brilliant set of individuals who brought varying perspectives to learn how to identify, analyse and address indirect discrimination. This positively impacts that protection of those who may be persecuted based on their sexual orientation and gender identity,” said Madrigal-Borloz. As he prepares thematic reports to the UN General Assembly and UN Human Rights Council on topics such as religion, colonialism, and the right to health, he will draw on such conversations to better understand such discriminatory practices and the intersectional response required to produce an effective and efficient response. Ultimately, he hopes this will lead to the common objective of eradicating violence and discrimination.